Dance Artists and Audiences Face a Dilemma: To Go or Not to Go to the Kennedy Center?

Diane DeFries, former executive director of the American College Dance Association, has been attending performances at The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts since it opened in 1971. At ACDA’s national festivals, she saw generations of students look awestruck upon walking into the imposing Washington, DC, performing arts center.

But she has no plans to set foot in its red-carpeted halls now. And she’s not alone. Since President Trump took over leadership of the venue in February—and especially since the recent firing of the Center’s dance programming team, and the installation of the self-described “MAGA former dancer” Stephen Nakagawa as the new director of dance programming—the question of whether or not to go to the Kennedy Center has become politicized. Vociferous calls to boycott the Center have spread across social media, leading to huge drops in subscription and advance ticket sales.

“Much to my despair, I feel like I cannot go to the Kennedy Center in good conscience at this point,” DeFries says. “The intention of this administration is to transform our national monument to the performing arts into an institution with values…that are counter to what the arts have been historically.”

The Kennedy Center is one of the largest performing arts centers in the U.S. Because of its capacity, reputation, and prominence as the country’s national cultural center, its programming in dance and beyond has vast influence. “It’s an important stage for America, and an important stage for the world,” says Alicia Adams, who was vice president of international programming and dance until she was let go in May.

Earlier this year, President Trump decried the Center’s programming as “woke,” and in August, while announcing the latest class of Kennedy Center Honorees, he leaned in: “We reversed what was happening. We ended the woke political programming and we’re restoring the Kennedy Center as the premier venue for performing arts anywhere in the country, anywhere in the world.”

Droves of dance and other performing artists, arts managers, and loyal Kennedy Center audience members appear to disagree. Many dancers and choreographers in the greater Washington, DC, metropolitan region, like DeFries, are weighing whether attending events there would be a tacit endorsement of President Trump’s policies.

Chris and Ama Law, co-directors of the Maryland-based dance theater company Project ChArma, grew up in the DC area but only recently began to feel like the Center was a place for them. In 2019, Jane Raleigh—then the Kennedy Center’s dance programming director, who made a concerted effort to broaden the representation of local dance companies across genres in Center programming—invited Project ChArma to present their piece Rooted at the Center’s Millennium Stage. The Laws were later invited to help curate 2023’s National Dance Day event dedicated to hip hop, and subsequently received a coveted Local Dance Commissioning Project award, which came with a $20,000 commission and a performance slot in the Center’s Terrace Theater.

Project ChArma is scheduled to perform Saturday, September 20, at this year’s National Dance Day. “But now I don’t know about buying tickets,” Ama Law says. “I’ll just do my damnedest to find comps, or wait for discounts…anything that gives the institution less of my money.” At the same time, the Laws are thinking about the impact of boycotts on dance artists. “I would hate to be that artist who is performing to an empty crowd, knowing how hard I worked,” Ama Law says.

Absent from this Kennedy Center season is Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, a perennial favorite engagement at the Opera House. Ailey week at the Kennedy Center not only frequently sold out, but the opening night company benefit has been a major fundraiser for Ailey, bringing in over $1.2 million this past February. This year the company opted to perform instead at DC’s Warner Theatre. It declined to comment on that decision.

Without strong ticket sales, dance at the Kennedy Center may not be sustainable. “In 2021 the pandemic crashed everything in terms of ticket sales and subscriptions,” Raleigh says. “In subsequent years we were seeing more robust subscriptions than many of our dance-presenting colleagues nationally. And our single tickets were selling in the 70-to-80-percent–capacity range for most of our [dance] engagements, some much better. Houses were full, we were feeling good about it.” She noted—and Adams confirmed—that the newly hired Trump-endorsed upper managers were very complimentary on dance programming earlier this year.

Raleigh plans on attending the 2025–26 season, which she partially booked. “ ‘Come see dance’ was my position when I was inside the Kennedy Center, and it remains my position now,” she says. “Support the artists who are on those stages and my colleagues who remain working at the Kennedy Center.” Adams, who spent three decades of her career in programming at the Center, says that she is also looking forward to supporting the dance companies she booked for the coming season. “If there’s something there that you believe in and respect, a company whose work you have supported or want to see, then support them,” she says. “Be in that audience to cheer them on.”

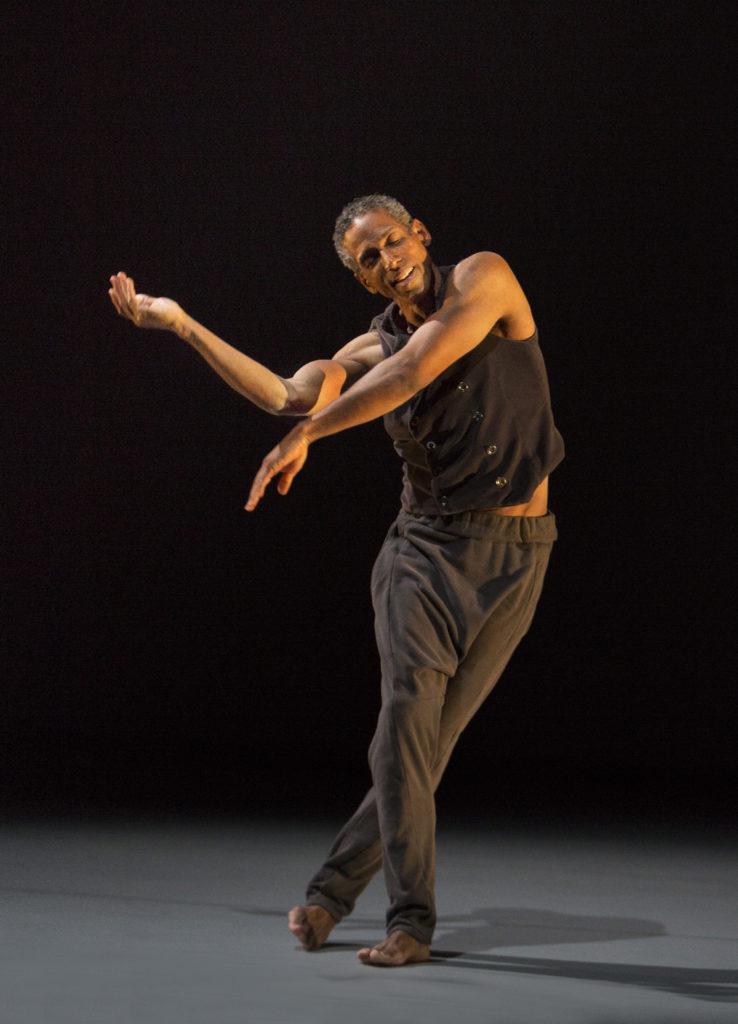

“To go or not to go,” however, remains the question. Vincent Thomas, a Baltimore-based dance artist and educator whose company, VTDance, has been presented on the Kennedy Center’s Millennium Stage, last came to a performance at the Center in August—one day after Raleigh and the rest of the dance programming team were fired. “I felt for these artists and I felt an obligation, a need, to support them,” he says. But Thomas, like many other formerly dedicated dance patrons, has yet to purchase tickets for the 2025–26 dance season.

The post Dance Artists and Audiences Face a Dilemma: To Go or Not to Go to the Kennedy Center? appeared first on Dance Magazine.